Time to look at some case studies of design activism. Let’s start with a couple of recent projects dealing with the issue of migration between the US and Mexico.

Day Labor Station

The first project is a day laborer station devised by a nonprofit architecture studio in San Francisco, Public Architecture. Covered in an article by Kirstin Palm in Metropolis Magazine (June 2007), the project grew out of observations by one of the studio’s members, executive director Tom Panelli. Upon seeing day laborers on street corners waiting for builders, contractors and homeowners to seek them out, he wondered about the whole system.

Portable “Day Labor Station,” courtesy Public Architecture

In addition to lacking basic amenities during their wait, the workers did not appear “as the skilled people they are. It looks like guys hanging out on a corner.” Public Architecture began combining their observations with interviews of day laborers asking what they could use, and the result was a portable day laborer’s station offering some comfort, humanity and dignity to this workforce. The station includes basic amenities, but also includes an open air meeting room for workers to take classes, meet or confer with employers.

Liz Ogbu, of Public Architecture, notes that some cities have set up worker centers for day laborers, but Day Labor Station constitutes a new model for the worker center. In contrast to conventional stationary and enclosed worker centers, the new station’s portability suits many workers and employers who see their work as “off the grid.” In addition, the station’s sheltered, yet open air structure provides visibility of the workers to the employers, another vital element in this system. The flexibility in the design allows for variations such as storage boxes under benches, a mini kitchen (to make food, possibly for sale “to go”).

Anatomy of the Day Labor Station activism

Recall that activism, for the purposes of this blog, is taking action (typically within the context of a contentious issue) intended to bring about change on behalf of a wronged, deprived or excluded group. In this case the designers took action on behalf of a typically excluded group (the article estimated there were about 117,000 day laborers in the US and most are from Mexico and Central America). They took action to bring about change – in this case improve workers’ access to basic amenities and offer legitimacy for a skilled workforce.

Did these activists succeed? The design proposal was unveiled at Cooper Hewitt’s show “Design for the other 90%” but at the time of writing had not been built. The designers are searching for the right fit – an early adopter. The fact that the design is getting major national exposure trains the spotlight on the issues, which increases the likelihood of getting the project built.

Hyperborder

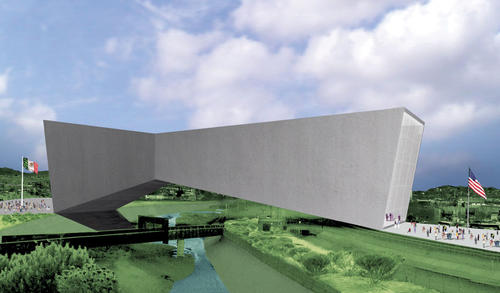

Mexican architect Fernando Romero was initially an activist for hire, commissioned to design a footbridge across the Rio Grande that would also serve as a museum of immigration. Also reported in Metropolis Magazine (December 2007 by Rebecca Cavanaugh), this story ended with Romero and his firm becoming much more interested in the notion of borders. They began exploring border issues far beyond architecture’s mediating role.

Bridge Museum across the US Mexico Border

courtesy LAR/Fernando Romero

In the end they propose a range of long term scenarios that demonstrate just how rich the relationship between the two counties might be if politicians could get beyond their reductive stances (unlikely in the near term). The research and proposals are presented in their book, Hyperborder: The Contemporary U.S. – Mexico Border and Its Future (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007).

(link to Amazon page)

Anatomy of hyperborder activism

Initially Romero’s activism for hire was on behalf of a group, immigrants and migrants, who have historically been deprived, if not actually excluded. The action of creating the bridge was ostensibly to improve understanding and appreciation of immigration issues (the museum) and provide an improved physical link between countries for all who cross back and forth. How successful was it? Like the portable laborer station above, it has not yet been built.

With the Hyperborder project, Romero and his studio entered into the role of proper activists. They started with the same immigrant/migrant/”guest worker” group, but their call for change became broader and more radical. In itself, the call to look at long term, big picture issues is radical and ranged across issues such as health care (should US retirees seek healthcare in Mexico because it is cheaper, the way British people seek health care in continental and eastern Europe because it is speedier – “healthcare tourism”?) and energy (should the US work with Mexico to concentrate development of low cost renewable energy there?) and so forth.

The book is also highly visual with side-by-side graphical comparisons of the two countries, humanizing portraits of individual migrant workers. In this way the designers’ actions makes a great deal of information visible, and therefore accessible in a way that it has not been before. How successful is it? The aim of this kind of activism is to build solidarity around an issue–to change the terms of the debate, reframe the language in the discussion. Success is hard to gauge, but their work was a runner up in Metropolis’ Next Generation Design Awards, suggesting that the message, the issues and the questions are, by virtue of becoming “news,” reaching a wider audience.

Conclusion

In their effort to humanize the migration and immigration issues, both these projects used portraits and profiles of real people to expand the story of the structures they were proposing. And in terms of their stories of activism, both cases raise some interesting issues.

First, what constitutes “success” for this activism? Is it enough to generate a proposal and get the issue widely covered? In some senses this coverage does help to frame public debate about immigration and migration issues, and changing the debate is the first step toward changing practices and policies, if not attitudes. It demonstrates that the “future visions” which designers are well suited to present can, without even being built, contribute to change. Do we rate the success more highly if the projects take the next step toward “built” change? How do we balance “design” criteria with criteria for social change?

Second, how are these instances of activism linked to broader social movements? This is something we don’t necessarily see in “design” coverage. But we know the issues of migration and immigration are not new and that there are a number of social movements addressing migrant and immigrant worker issues. When and how should design activist efforts link back into these social movements?

Third, in many cases we find that design activists start out as activists for hire. Some go on to become activists in their own right. Others don’t. How can designers balance an activist agenda within their own work? The examples above show that one group formed a “social” practice with activist intentions at the start. The other group gained a commission that launched their own, original activist project.